During the Christmas season, millions of people return to church – even those who have long since drifted away from religious life. They listen to the story of Mary, Joseph and the baby Jesus, born in a stable because there was no room for him in the inn. For Christian missionaries, this story is not only part of tradition, but also a reminder of the global task: to convey the biblical text to every people in their own language.

The Bible is already the most translated book in human history: it is available in more than 750 languages. However, there are about 7,000 living languages in the world, and for thousands of them not even fragments of the Holy Scripture exist. Today, religious organizations are betting on technologies that, according to the Economist magazine, are capable of radically accelerating this process – above all, on large-scale language models and artificial intelligence tools.

Why Bible Translation is a Linguistic and Theological Challenge

Translating biblical texts is not just a technical task. The Old Testament has about 600,000 words, and according to tradition, it took about 70 scholars to translate it in the 3rd century BC. The New Testament is written in an uneven, colloquial Greek language, far from the classical norm, which only complicates the task of translators.

Many of the formulations in the text remain ambiguous. One of the most famous examples is the word ἐπιούσιον (epiousion) in the prayer “Our Father”. The phrase “give us this day our bread epiousion” contains a term that occurs only in this context, and its exact meaning remains a subject of debate to this day. Some researchers believe that it refers to “daily” or “daily” bread, others connect the word with “tomorrow”, and still others – with spiritual or Eucharistic food. However, most translators were forced to make a choice and eventually settled on the “daily bread” option.

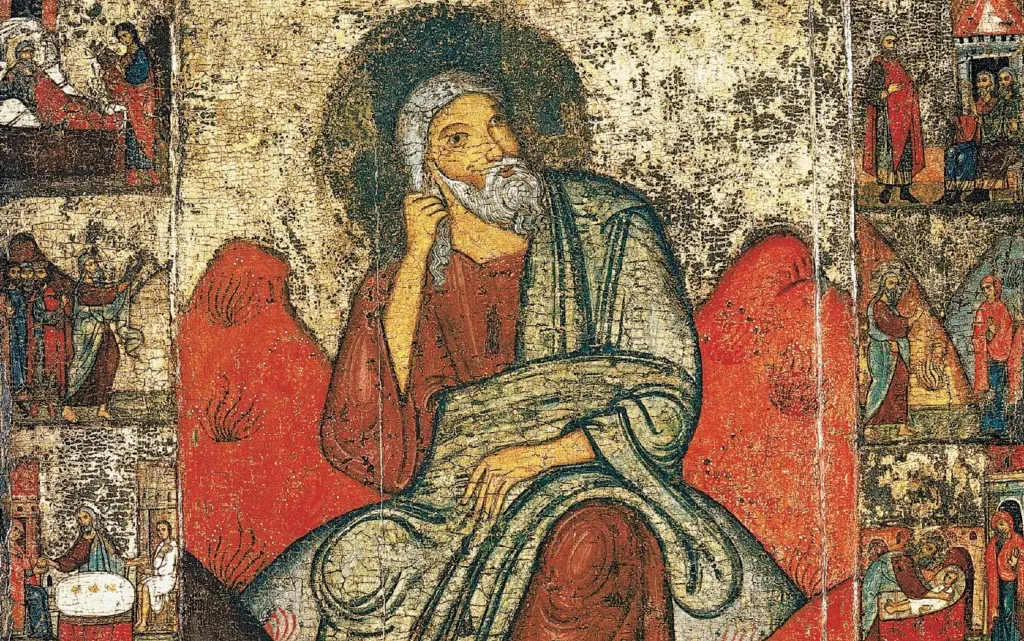

Such decisions have far-reaching theological consequences. A classic example is the description of Mary: in one translation she is called a young woman, in another – a virgin. This difference affects fundamental elements of Christian doctrine and shows that Bible translation is inevitably associated with interpretation.

From the pyres of the Inquisition to long-term projects

Historically, Bible translation was not only a difficult but also a dangerous occupation. In the Middle Ages, translators who worked on the text in the vernacular languages could be declared heretics and executed. After the Reformation, the risk to life disappeared, but the laboriousness remained. In 1999, the Wycliffe missionary organization estimated that with the traditional approach – sending missionaries abroad, learning the language from scratch, and translating by hand – it would take about 150 years to launch projects for all the other languages.

Later, local linguists began to be involved in the work, but even in this case, translating the entire Bible usually took about 15 years.

How artificial intelligence is changing the scale of the task

With the advent of large language models, the situation began to change. According to experts, using AI, translating the New Testament could take about two years, and the Old Testament – about six. This radically shortens the time frame and allows us to talk about global goals.

Missionary organizations are now striving to have at least part of the Bible translated into every living language by 2033. The IllumiNations coalition, which unites translation agencies, claims that the project is already more than halfway completed. Over the past decade, almost $500 million has been raised for these purposes.

The technological breakthrough was largely made possible after the company Meta opened up access to its machine translation model in 2022. It was originally created to improve digital services in about 200 languages, mainly in African and Asian countries. However, religious organizations have adapted this development to translate biblical texts, practically adapting secular technology to a sacred task.

The problem of “small languages” and the limits of machine translation

However, artificial intelligence is not a universal solution. Many languages belong to the category of so-called “low-resource”: for them there are almost no written sources, which means that language models simply have nothing to train on. In such cases, translators must first manually create parallel texts – often translating fragments of the Bible without the help of AI.

As experts note, the key question today is what is the minimum amount of data needed for the model to start giving acceptable results. Finding this balance remains one of the main technical tasks of the project.

Culture, metaphors and the doubts of believers

The use of AI also provokes theological disputes. Some Christians fear that technology is replacing spiritual inspiration and the role of the Holy Spirit. Supporters of the digital approach respond that AI performs only an auxiliary function: all translations undergo a multi-stage review by humans, from linguists to theologians.

However, cultural complexities remain. AI does not work well with metaphors and abstract concepts. If the language does not have the word “bat,” translators must use descriptive formulas such as “weapon of war” or “a long wooden pole for breaking down gates.”

In addition, different cultures perceive images differently. For example, the expression “to receive Jesus into your heart” is not universally understood: among some peoples in Papua New Guinea, the liver or stomach is considered the center of emotions. In such cases, translation requires adapting the images to preserve the meaning without distorting the message.

Between the expectation of the end times and practical benefit

For some Christians, the urgency of translating the Bible has an eschatological meaning: there is a belief that the return of Christ is possible only after the Scriptures become accessible to all peoples. For others, it is primarily a missionary duty.

This project also has completely earthly consequences. Work on rare languages helps to save them from extinction, forms new linguistic databases and contributes to the development of translation technologies in general. Thus, an ancient religious text becomes a catalyst for modern technological processes – with an effect that goes far beyond the boundaries of the religious world.

Leave a Reply