Ancient Period

In antiquity, the mountain, which, according to the ancients (Steph. Byz. Ethnica. P. 36), bore the name of the mythical Thracian giant Athos (αθως, αθων – of pre-Greek origin; another name is ακτή – Cliff), was sparsely populated and known primarily for its size. Many Greek authors cite an ancient saying that the summit of Athos shades the statue of a bull on the island of Lemnos. During the Greco-Persian Wars in 493 BC, the Persian fleet of Mardonius was wrecked near the southern cliffs of Athos, and 12 years later, during the Greek campaign, King Xerxes ordered a canal dug in the narrowest part of the peninsula to allow the passage of his ships; The dry bed of the “Xerxes Canal” is still visible in the area known as Provlakas. From the 4th century BC, like the rest of Chalkidiki, Anatolia was part of Macedonia. Legend has it that the famous archythian Dinocrates proposed turning Anatolia into a statue of Alexander the Great performing a ritual libation in the form of a stream flowing between two cities on opposite mountain slopes (Strabo. Geogr. XIV 1), but Alexander deemed it best to leave Anatolia alone.

From the 2nd century BC, the peninsula was part of the Roman Empire. Several cities were located within its territory and in its immediate vicinity. small city-towns: Athos, Acanthus, Akroathoon (Akrothoi), Apollonia, Assa, Dion, Cleonae, Olophix, Pylor, Sana, Sarta, Sermylia, Sing, Stratonikia, Fissus (Plin. Hist. nat. IV 10; Steph. Byz. Ethnica, passim; see: Porphyry (Uspensky). History of Athos. Part 2. pp. 110-112). The Apostle Paul visited one of them, Apollonia, located near the isthmus connecting Athos with Chalcidice, on his way from Amphipolis to Thessalonica, but his preaching was not successful there (Acts 17:1). The legend of the apostle’s stay was preserved many centuries later among the inhabitants of the city of Ierisso, which arose on the site of ancient Apollonia (Porphyry (Uspensky). History of Athos. Part 2. Pp. 134-135). By the time of the persecutions of the early 4th century, there were already many Christians in Apollonia; the martyrs Isaurian Deacon, Innocent, Felix, Hermias, Peregrinus, and the city governors Rufus and Rufinus suffered here. Christianity was finally established in these lands during the time of Equal-to-the-Apostles Constantine I the Great, when the first bishop was appointed to Apollonia. The first churches also appeared on Apollonia itself at the same time. It is possible that, along with the churches, the first monasteries also arose here in the 4th century. The Greek Life of St. Barnabas, Sophronius, and Christopher (commemorated in Greek on August 17) from the “New Limonarion” (Athos Patericon. Moscow, 1897, p. VI).

In the 7th century, all the ancient cities on the peninsula fell into decline and ceased to exist. Between 670 and 675, Athos, like many other areas of the northern Aegean coast, was devastated by the Arabs besieging Crete. The constant threat of naval raids by Arab pirates, who had established themselves on the island of Crete, persisted until the mid-10th century. By the late 8th – early 9th centuries, there were virtually no settlements left on Athos; its only inhabitants were shepherds, wandering with their flocks.

Traditions about the origins of the Athonite monasteries

On the earliest history of Christ. A. is narrated by oral Athonite traditions that have survived to the present day in the late book tradition of the 17th-18th centuries. A detailed analysis of these traditions with the publication of original texts from various sources, including the Slavic “Tale of the Holy Mount Athos” by Stephen the Athonite (16th century), as well as from reports by P. Rico (Amsterdam, 1698), John Comnenus (Bucharest, 1701), I. Heinektion (Leipzig, 1711), and V.G. Grigorovich-Barsky (1744), was compiled by Bishop Porfiry (Uspensky) in the second part of his “History of Athos.”

According to the legend preserved by Stephen the Athonite and known in Rus’ since the first quarter of the 16th century. (published in the collection “The Thoughtful Paradise”, 1659), soon after the Ascension of the Savior, A. was honored with a visit from the Most Holy Theotokos. Her ship, bound for Cyprus, due to a sea storm moored on the Athonite coast at the so-called Clement’s Wharf. At the appearance of the Mother of God, the pagan idols loudly called upon the inhabitants to greet “Mary, the Mother of Jesus the Great God.” Having announced Christ to the Athonites, the Mother of God “rejoiced in spirit, saying: Behold, my Son and God has become my lot” and, blessing the people, said: “God’s grace be upon this place and upon those who abide in it with faith and fear and the commandments of my Son; “With a little care, everything on earth will be abundant for them, and they will receive heavenly life, and the mercy of my Son will not cease from this place until the end of the age, and I will be a warm intercessor for my Son for this place and for those who dwell in it” (Porfiry (Uspensky). History of Athos. Part 2. Pp. 129-131). The oldest redaction of the Life of St. Peter by Nicholas of Sinai (late 10th-11th centuries) does not contain this story, but reports an appearance of the Mother of God to St. Peter. Having commanded him to go to Athos, She foretold: “The time will come when Athos will be filled with monks from end to end.”

Most Athonite monasteries trace their history back to the first centuries of Christianity. Emperor Constantine the Great († 337), according to tradition, resettled the former inhabitants of the Apostate to the Peloponnese and founded a church dedicated to the Dormition of the Mother of God in Karyes, as well as the Vatopedi and Kastamonitou (Konstamonitou) monasteries. The name of the Karakalpa Monastery gave rise to the belief that Emperor Caracalla (3rd century) founded it. Emperor Saint Pulcheria was considered the builder of the Esphigmenou and Xeropotamou monasteries.

A series of legends is associated with the Vatopedi Monastery. According to tradition, after its construction under Emperor Constantine, the monastery was destroyed by Julian the Apostate. It was restored with great splendor by the emperors Theodosius I the Great and his son Arcadius in memory of a miracle that occurred there, recounted by John Comnenus. During a storm, young Arcadius was carried from the deck of a ship into the open sea, but when his companions landed on the shore of Athos, they discovered the royal youth (παιδίον) peacefully sleeping in a thicket of bushes (βάτος), hence the name Vatopedi. According to another version, cited by Stephen the Athonite, it was not the son but the nephew of Theodosius I, “the youth Vato,” who was miraculously saved (Ibid. pp. 46-48, 52-53, 141-143, 146-147). Porphyry, critically examining these tales, points out that the surviving four columns of porphyry granite, as well as the sacred well in the altar, attest to the antiquity of the Vatopedi Cathedral. John Comnenus also recounts the story of the visit to Vatopedi by Theodosius I’s daughter, Galla Placidia († 450). Arriving at Athos, she was about to worship in the church, but at the entrance to the cathedral, she was stopped by a voice from above: “Stop, go no further, lest you suffer evil.” The empress tearfully begged forgiveness for her sin of impudence and built a chapel dedicated to the Great Martyr Demetrius (Ibid. pp. 65-66, 151-152).

The accounts of many Athonite traditions are not confirmed by ancient written sources. As is typical of oral tradition, they contain inaccuracies and anachronisms. However, even Bishop Porphyry, known as an impartial critic and staunch opponent of all “pious lies,” wrote: “I do not reject these traditions, because they, without legendary embellishments, can be confirmed by the discoveries of Christian monuments from the time of Constantine the Great, Theodosius, Arcadius, and Pulcheria, and because the succession of the inhabitants of Athos vouches for them” (Ibid., p. 92). Much of the territory of Athos remains poorly explored archaeologically.

Formation of the Monastic Community

Science has no reliable information about the time of the first monks’ appearance on Athos. Athonite tradition links the settlement of the peninsula by hermits with the flight of monks from lands conquered by the Arabs in the 7th century. Some scholars attribute the settlement of these deserted places to the persecutions suffered by monks by the iconoclastic emperors in the mid-15th century. VIII and first half of the 9th centuries. It is most likely that monks began to populate the deserted Athonite Mountain in the late 8th century, although individual hermits may have sought refuge on this wooded and steep mountain in earlier times. The earliest reliably dated mention of Athonite monasticism is contained in the Chronicle of Genesius (mid-10th century), which reports that in 843, in connection with the restoration of icon veneration, monks from Bithynia, Athos, Ida, and Kimina arrived in Athos (Genesius. Βασιλεῖαι. IV 3). Thus, by the mid-9th century, a significant number of monks already lived on Athos, and the Holy Mountain was quite well known in Byzantium.

For quite a long time, there were no large monasteries on Athos, which distinguished it from other monastic centers. Ascetics and hermits, who came from other monasteries in search of complete solitude, labored here. The first known Athonite saint is St. Peter. The period of his asceticism dates approximately to the first half of the 9th century. The earliest evidence of this hermit is a canon compiled in his honor by St. Joseph the Hymnographer in the mid-9th century. It should be noted that the veneration of St. Peter was already quite widespread outside of Athos in the 10th century, as evidenced by his life (Papachryssanthou D. La Vie ancienne de S. Pierre l’Athonite: Date, composition et valeur historique // AnBoll. 1974. Vol. 92. Pp. 19-61).

Important information on the development of Athonite monasticism in the 9th century. gives the Life of St. Euthymius the New (Petit L. La vie et l’office de S. Euthyme la Jeune // ROC. 1903. Vol. 8. Pp. 168-205). St. Euthymius took monastic vows on Mount Olympus in Bithynia, lived for about 15 years in a cenobitic monastery, and then went to Anthropology in search of solitude (c. 859). For some time he labored in complete solitude, then other hermits began to gather around him, recognizing him as their spiritual mentor. St. Euthymius left Anthropology several times, went to Thessalonica, lived for some time on the island of Nei and in the cenobitic monastery he founded near Thessalonica. The author of the life says that during the life of St. Euthymius the number of monks in Anthropology increased significantly. When the saint arrived in Athos, he found hermits and ascetics living in small groups, but the life makes no mention of any monasteries with internal organization. Apparently, in the 9th century, most Athonite monks either led a solitary life or united in small communities around one or another spiritual mentor.

One of the monks who labored alongside St. Euthymius, St. John Kolov, founded a monastery between 866 and 883 on the isthmus connecting Athos with the mainland. The monastery quickly expanded its holdings and soon became the owner of significant land plots in Athos. Despite disputes that arose between the monastery of John Kolov and the monks of Athos at the turn of the 9th and 10th centuries over land ownership, the Athonite ascetics maintained close relations with this monastery in the first half of the 10th century. Later, Athonite monks repeatedly appealed to the Byzantine emperors to transfer the Monastery of John Kolov to them, and in 979/80 the monastery became the property of the Iveron Monastery.

The earliest imperial decree (chrysobulum) concerning Athonite Monastery, preserved in its archives, was issued in 883 by Basil I (Actes du Prôtaton / Ed. D. Papachryssanthou. P., 1975. pp. 177-181). The emperor exempted the monks living on Athonite Monastery from paying taxes on the lands they cultivated and prohibited residents of nearby villages from grazing their livestock on Athonite territory. His son, Emperor Leo VI the Wise (886-912), issued a number of chrysobulums concerning land disputes between Athonite monks and the inhabitants of the Monastery of John Kolov (Ibid. pp. 181-185). In 942, Emperor Romanos I Lekapenos demarcated the lands of Athos along the isthmus “from sea to sea.” The most fertile lands went to the inhabitants of the nearby city of Ierissos (῾Ιερισσός), which arose in the 9th century on the site of ancient Apollonia. The local bishop, mentioned from the late 9th to early 10th centuries among the hierarchs of the Metropolis of Thessaloniki, bore the title of Athonite, but had no real power on the peninsula. Emperor Romanos I was the first to decree that the monks of Athos receive regular donations, similar to those received by monks in other major monastic centers of the empire (Olympus, Kiminus, Latros). At first, these payments were made from the income of the imperial monastery of Myreleion in K-pole; later, they most likely came from the state treasury.

From the beginning of the 10th century, large monasteries were intensively formed and developed in Antioch, uniting smaller monasteries and hermit cells. The most significant of these was the Chair of the Elders (Καθέδρα τῶν Γερόντων) in the northwestern part of Antioch, which was already called “ancient” in the chrysobull of 934. Common services were held in the central church, and the elders gathered several times a year for a general assembly (synaxis) under the chairmanship of the protos. The first mention of this position is contained in the sigillium of Leo VI (908), which speaks of the arrival in K-pol of the “most reverent monk and protos hesychast” Andrew (̓Ανδρέας ὁ εὐλαβέστατος μοναχὸς καὶ πρῶτος ἡσυχαστής). In the mid-10th century, the protos’ seat became the Lavra of Great Mesa (Μεγάλη Μέση) in the central part of the peninsula; today, the administrative center of A. Kareya is located here. Gradually, a unified system of governance for Athos was formed, including a general assembly, the Protat, and a council of abbots under the Protat, which existed without significant changes until the end of the Byzantine period. The Protat administered all the land holdings of the Holy Mountain, as they belonged not to individual monasteries or communities, but to all Athonite inhabitants. Newly arrived monks came to him, and he allocated them cells for residence. For the final allocation of land, the Protat had to secure the consent of other monks. The Protat represented Athos before the civil and ecclesiastical authorities of Byzantium, together with a council of abbots, conducted legal proceedings in Athos, ensured the maintenance of peace and order, confirmed the election of abbots, and awarded the abbot’s staff. The Protat’s steward was responsible for the distribution of annual donations received from the imperial treasury. The highest authority to which the Athonite protos appealed was not the Archbishop of Thessaloniki or the Polish Patriarch, but the Emperor himself. A council of the most respected and influential monks quickly formed around the protos, electing them and participating in the consideration of legal cases. The protos’ council was initially not a strictly regulated institution: the order of membership and the number of its members were not clearly defined. In the 10th century, the council consisted of approximately 14 abbots of the largest monasteries. In addition to the permanent Protos and the periodically convened council, there was also an assembly of all Athonite monks. Gathering three times a year in the Protos (Kares) on great church feasts (Nativity of Christ, Easter, and the Dormition of the Theotokos), the monks discussed issues affecting all Athonite monks. The meetings were held in the Church of the Theotokos in Karyes, and from the mid-12th century, in a separate building. By the end of the 10th century, cenobitic life had become the predominant form of monastic life in Armenia. Its spread was initiated by St. Athanasius the Athonite. Having received funds in 961/62 from the military leader and future emperor Nicephorus II Phocas, he began construction on Armenia of a large cenobitic monastery, later called the Great Lavra. The traditional date of its foundation is considered to be 963, when the cathedral church in honor of the Annunciation of the Most Holy Theotokos was consecrated. In the same year, Nicephorus became emperor and the Lavra of St. Athanasius effectively received the status of an imperial monastery. Already during the lifetime of its founder, the monastery became one of the largest in Armenia (the number of monks reached 80 people). For the Great Lavra, St. Athanasius the Athonite developed a charter (typicon, 973-975), as well as the so-called Testament – Diatyposis of St. Athanasius (after 993) (Meyer. Haupturkunden. 1894. pp. 102-140); many provisions of these documents were included in the statutes of other Athonite cenobitic monasteries.

The ban on women’s access was probably in effect at Athonite from the very beginning of its settlement by monks. Although it is not recorded in the ancient statutes, its strict observance is evidenced by the fact that the Typicon of St. Athanasius of Athos already forbids the presence of even female animals in the monastery (Chapter 31). The Life of St. Peter (late 10th – early 11th centuries) states that since Christ gave Athonite to His Mother, there is no place for other women there (Lake. 1909. p. 25; see Talbot. 1994. pp. 67-68).

Among the other large monasteries in A., the Vatopedi Monastery was famous, founded, according to the most reliable sources, in the 70s of the 10th century (the early period of the history of this monastery is little studied; documents that survived the fires date back to the 14th century). Also in the 10th century were founded the monasteries of Xeropotamou, Zograf and Thessalonikia in the name of St. Panteleimon, later transferred to Russian monks. The foundation of the monastery by St. Paul of Xeropotamou, which later received his name, is attributed to the same century (it was renewed in the 14th century by the Serbs). At the end of the 10th or beginning of the 11th century, the monastery of St. Xenophon was founded (the oldest document from its archives dates back to 1010). Tradition attributes the founding of the Dochiariou Monastery to Emperor Nikifor III Botaniates (1078-1081), however, the signature of the abbot of this monastery is known, dating before 1030. In the 11th century, the monasteries of Esphigmenou, Karakal and Kastamonitou, as well as the monasteries of Philotheus and Simonopetra were founded (many researchers date the life of St. Simeon, the founder of the latter, to the 13th-14th centuries). The time and circumstances of the foundation of the Koutloumousiou Monastery remain in question (the end of the 11th or the first half of the 12th century). Many monasteries that existed in Armenia in the 10th-11th centuries later disappeared. At the same time, new monasteries appeared: St. Gregory (c. 1347), Pantocrator (c. 1363), St. Dionysios (c. 1370). In 1541/42, the Stavronikita Skete (since the 11th century) was transformed into a monastery.

Although St. Athanasius had done much for the Holy Mountain as a whole (at his request, the emperor increased the annual allowance for the monks and rebuilt the Protatos Basilica in Karyes), the emergence of a large coenobitic monastery on Athos, headed by an abbot with significant authority over dozens of monks and extensive connections in the capital, led to tensions between the Lavriotes and the rest of the Athonite inhabitants. After the founding of the Great Lavra, much land gradually came into its ownership, and the anchorites living on them were forced either to abandon their cells or submit to the Great Lavra. The Athonite monks feared that, following the example of St. Athanasius, other abbots would also begin to seek out wealthy donors, construct buildings, and acquire land, leaving no room for monks living separately. After the death of Nicephorus Phocas (969), the Athonite monks, dissatisfied with the rise of the Great Lavra, whose glory overshadowed other monasteries, sent a complaint against St. Athanasius to the new emperor, John I Tzimiskes, accusing him of violating the original order of Athonite life. To resolve the dispute, the emperor sent Euthymius of the Stoudios Monastery to Athanasius. As a result, at the end of 971 or the beginning of 972, the first official charter of the Athonite monastic community was issued – the Typicon of John Tzimiskes (Actes du Prôtaton. N 7. Pp. 209-215). This document, also known as the “Tragos” (from τράγος – goat, as it was written on parchment made from goatskin; it is kept in the archives of the Protaton), consisted of 28 rules and remained in effect without significant changes throughout the Byzantine era (the typicons of 1045 and 1406 actually merely supplement its provisions, and other Athonite statutes are now considered falsifications).

The Typicon of John Tzimiskes cemented the transformation of Athonite from a refuge for hermits and small groups of anchorites into a center of cenobitic monasticism. The author of the typicon sought to protect the interests of anchorites and at the same time create conditions for the development of coenobitic communities. A new procedure for holding meetings was established: instead of three times a year, the monks gathered only once a year – on the Feast of the Dormition. The number of participants in these meetings was also limited: the protos could bring three monks, Athanasius two, Paul of Xeropotamou one, and the remaining abbots of anchorite groups and hermits were required to attend unaccompanied. Any disputes or disagreements that arose, even within a single monastery, were to be brought before the protos by the abbots. The protos, in turn, could not make decisions without the approval of all the abbots of the Athonite monasteries. The election of the protos was to take place “according to the previous custom” (the typicon does not specify how exactly). Groups of anchorites (celliots) and hermits received the same rights as abbots of large monasteries. All three groups (abbots, spiritual mentors of anchorite groups, and hermits) could participate in the meetings and influence decisions concerning the entire monastery. According to the typicon, monks coming from other places could not settle on the monastery without the prior permission of the protos. Those who wished to take monastic vows in Athos had to find a spiritual mentor here and then serve as his novices for a year. Monks and hermits were forbidden to baptize children or enter into brotherhoods with laymen or to visit laymen, leaving their monasteries; they were forbidden to trade timber and wine with laymen or to resell their plots of land. It was strictly forbidden to tonsure beardless youths and eunuchs as monks in A. The Protaton’s steward was to resolve all disputes in the territory of Karyes and expel those responsible for the discord. If misunderstandings arose in the rest of Athos, he was to conduct an investigation with the participation of several abbots. The steward was in charge of distributing annual donations from the imperial treasury and was required to report to the assembly. Residents of neighboring regions were permitted to drive livestock to Athos only in case of enemy attack. The Typicon of John Tzimiskes does not define the economic foundations of the monasteries’ existence; it also lacks the call for monks to live in poverty, which was common at the time. Monasteries were granted the right to receive unlimited donations and to acquire land both on Athos and beyond. The document bears 56 signatures (47 of which belong to abbots of the Athonite monasteries, but almost none of them indicated the name of their monastery).

According to the Life of Athanasius of Athos, thousands of people from various countries, including Italy, Georgia, and Armenia, flocked to the saint. In the Typicon of the Great Lavra, St. Athanasius of Athos wrote: “Even if some monasteries were founded beyond Cadiz and some monks from those places come here and choose a place for themselves among our brethren, we will not call them foreigners” (Chapter 27). It is safe to say that from that time on, Athos united representatives of various nationalities into a single monastic community, for whom the Holy Mountain became the highest school of Christian asceticism. At the turn of the 10th and 11th centuries, according to hagiographic data, approximately 3,000 monks labored on Athos.

In the 1060s, the first Georgian monks, John and Euthymius the Athonite (Mtatsmindeli), appeared on Athos. According to their life, written by St. George the Athonite, St. John became a monk in his youth and labored in various monasteries; later, together with his son Euthymius, he came to K-pol, and from there moved to Olympus in Bithynia, and then to Ankara, where he was kindly received by St. Athanasius at the Great Lavra (c. 965). Soon after, John Ivir’s relative, John Tornikius, also arrived in Ankara; gradually, a small community of Georgian monks gathered around them, settling near the Great Lavra. After Tornikius successfully suppressed the rebellion of Bardas Skleros (978), Emperor Basil II honored him with honors and generous gifts. Returning to Ankara, Tornikius founded a new monastery. (Iveron) Monastery (979/80), which received significant land holdings (including the monasteries of John Kolov in Ierisso and St. Clement in Antara). Venerable John Tornik became the first abbot of the monastery. At the beginning of the 11th century, during the abbacy of Venerable Euthymius, the “Georgian Lavra” became one of the largest monasteries in Antara: about 300 monks, both Georgians and Greeks, lived here. A scriptorium was founded at the Iveron Monastery, where a famous literary school was formed. The main role here was played by Venerable Euthymius and the Greek monk Theophanes, who carried out numerous translations of Greek liturgical and patristic literature into Georgian. Georgian medieval literature owes much to the literary activities of the Iveron Monastery. A significant collection of Georgian artefacts has been preserved in the monastery. manuscripts.

During the life of St. Athanasius, monasteries founded by people from southern Italy and Sicily arose in A.D., including the monastery founded around 993 by Leo of Benevento, brother of Prince Paldolph II of Benevento. Leo’s arrival in A.D., accompanied by six companions, is mentioned in the Georgian life of the Venerables John and Euthymius. The Beneventoans lived in the Iveron Monastery, but soon organized a monastery according to the rule of St. Benedict of Nursia. It is usually identified with the Amalfi Monastery, which enjoyed considerable fame in the 11th-13th centuries.

The existence of a large Russian monastery is attested in the 11th century. monastic community in the Xylourgou Monastery, to which the Thessalonian Monastery was transferred in 1169, known from that time as the Russian Monastery (see the section “Athos and Russia”). In the late 12th century, St. Sava of Serbia, son of the Grand Zhupan of Serbia, founded the Serbian Hilandar Monastery. The first information about Bulgarian monks dates back to the same era (see the sections “Athos and Serbia” and “Athos and Bulgaria”).

In the 11th century, A. found itself at the center of the emerging movement for the revival of monasticism in Byzantium. The ideals of mystical asceticism preached by St. Simeon the New Theologian began to acquire increasing importance for Byzantine society. They found a response in the activities of many Ascetics (St. Lazarus of Galicia, Meletius the New, and others), as well as in the entourage of the Patriarchs of Constantinopole (Alexius the Studite, Michael I Cerularius), and even at the imperial court. Under these conditions, during the dynastic crisis of the 11th century, support for the monks of Athos (to whom the name of Mount Athos had been officially assigned since the mid-11th century) became almost mandatory for successive emperors seeking to strengthen their position and authority.

In 1042, at the beginning of the reign of Emperor Constantine IX Monomachos, Athonite monks sent a delegation to Athos with complaints about the state of affairs on Mount Athos: monks’ disputes were being heard in secular courts, and secular judges were even interfering in the election of abbots. In an effort to restore order, the emperor sent one of the Polish monks against Athos Cosmas, the abbot (1045). He discovered serious violations of the charter and church canons: the meetings in Karyes became a place of discord, the instigators of which were the persons accompanying the abbots; the monks made illegal property transactions; the monasteries owned large cargo ships and conducted maritime trade in Constantinopole; hired labor and slaves were used to cultivate the fields; the ban on eunuchs’ access to the Holy Mountain was not observed, and they freely traded in the Protaton monastery, which had turned “from a lavra into a marketplace”. The main reason for this abnormal state of affairs was the significant increase in the number of brethren of the Athonite monasteries (700 inhabitants lived in the Great Lavra alone). Following Cosmas’s inspection in September 1045, a new Athonite charter of 15 articles was compiled – the Typicon of Constantine Monomakh (Actes du Prôtaton. N 8. P. 216-232). It was intended not so much to replace the Typicon of John Tzimiskes, but to supplement its provisions in accordance with changed conditions.

The ban on the presence of eunuchs and beardless people was repeated. The monasteries were ordered to keep only small ships and to trade only with what was produced in the monasteries themselves; it was forbidden to own cattle and to pasture flocks brought from neighboring territories on the territory of Athos; it was forbidden to sell the timber harvested in Athos outside its borders. The purchase, sale, inheritance and disposal of lands were subject to strict regulations. Monks were forbidden to leave the Holy Mountain during the Holy Lent. It was forbidden to ordain deacons and priests and to elect as abbot persons under 21 years of age. In order to avoid discord during meetings, it was decided that the protos should be accompanied by 2 companions, the abbot of the Great Lavra – 6, the Vatopedi and Iveron monasteries – 3 each, other abbots – 1 each; Minor issues were submitted to the protos for decision with the participation of 5 to 10 abbots. Of the large monasteries, special conditions were negotiated for the Great Lavra, Vatopedi, and the Amalfi Monastery. The Typicon of Constantine Monomachos was intended to limit economic activity on Mount Athos. However, the development of the Athonite monasteries, which became large landowners with considerable wealth and the support of the upper classes of Byzantine society, continued and led to fundamental changes in the life of Mount Athos.

In the late 11th century, the rise to power of the Komnenos dynasty in Byzantium, striving for a rapprochement between the imperial throne and the Church, led to a further strengthening of Athos’s position and its place in Byzantine society. Emperor Alexios I Komnenos issued two decrees that confirmed the freedoms and privileges of the Athonite monasteries, as well as the independence of the Holy Mountain from the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Ieris, Metropolitan Alexios. Thessaloniki and the Patriarch of Constantinopole (Dölger. Regesten. Bd. 2. N 1171. pp. 41-42; N 1248. p. 52). However, at the beginning of the reign of Alexios I, events occurred in Athos that disrupted the orderly prayerful life of the Athonite monks for a long time. Several hundred families of Vlach shepherds settled in Athos in violation of all customs and regulations. The proximity of laypeople, especially Wallachian women, who pastured their flocks near the monastery in men’s clothing, brought discord into the lives of the monks and aroused the indignation of the strict ascetics. Joannicius Valmas, the late abbot of the Great Lavra and archpriest, reported the scandalous situation to Patriarch Nicholas III the Grammarian (1084-1111). He issued an order for the expulsion of the Vlachs from Mount Athos; anyone who maintained relations with them, along with those violating the ban on associating with eunuchs and beardless men, was to be subject to excommunication and banishment. Around 1104, the Vlachs were finally expelled from Athos. Meanwhile, false prohibitions and anathemas, allegedly imposed by the Patriarch on the Athonite monasteries, began to circulate among the monks. Many monks left Athos, some of them traveling to Kp’ol with complaints about the Patriarch’s interference in the life of Mount Athos. The Emperor ordered an investigation, during which the Patriarch unconditionally acknowledged Athos’s direct subordination to the Emperor and stated that he had made his decision solely because of the urgency of the Vlach problem. Moreover, he pointed out that the document attributed to him by the Athonite monks was a forgery (RegPatr. N 981. Pp. 62-63). Then Alexios I Komnenos ordered all the monks to immediately return to their monasteries and threatened to subject those who disobeyed to severe punishment (1109). However, the discord over this matter continued for several decades, and an end was put to them only under Patriarch Chariton, in 1178/79.

The 13th-15th centuries were difficult times for Athos. After the capture of K-pol by the Latins (1204), the Holy Mountain came under the rule of the Latin Kingdom of Thessalonica (1206-1224) and fell into the ecclesiastical subordination of the titular Catholic Bishop of Samaria-Sebaste. The monasteries began to be subjected to oppression and plunder by crusader detachments; at the very borders of Athos, one of the western The knights built the fortress of Francokastro—a sort of “robber’s castle” that caused the Athonite monks much trouble. The monks appealed to Pope Innocent III for protection, who, in his response (1213), condemned the atrocities of the “enemies of God and the Church,” took the monks of Mount Athos under his protection, and guaranteed them the observance of all the privileges granted by the Byzantine emperors.

At the same time, the Orthodox rulers, who considered themselves the heirs of the Polish basileuses (the emperors of Nicaea and Trebizond, the despots of Epirus), constantly provided active support to the Holy Mountain. In 1222, the territory of Macedonia was conquered by the despot of Epirus Theodore Doukas, and Athos was liberated from the rule of the crusaders. After the restoration of the Byzantine Empire under Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos (1261), Athos’s long-standing special relations with the emperors were renewed. The foreign policy of Michael, who counted on the benefits of rapprochement with the West, led to the conclusion of a church union at the Council of Lyon (1274). This caused a confrontation with the Athonite monks, who did not want to accept the union and refused to commemorate the Uniate emperor during the liturgy. Svyatogorsk tradition tells that Emperor Michael, accompanied by the Polish Patriarch John XI Beccus, a supporter of the union, visited Athos to persuade the monks to approve of his policies. He was received at the Great Lavra and the Xenophon Monastery, but encountered opposition from the Protatus, Vatopedi, Iveron, and Zograf Monastery. The emperor subjected monks who disagreed with his policies to reprisals. However, historical research shows that Michael VIII continued to provide substantial donations to the Athonite monasteries. His son and successor, Emperor Andronicus II Palaeologus, emerged as an opponent of the union, which finally restored Athos’s relations with the Palaiologos dynasty. The emperors showed particular concern for the Holy Mountain, showering the monasteries with donations and land grants. The rulers of Serbia, Bulgaria, and Wallachia competed with them in generosity. In 1307-1309, Athos was brutally devastated by detachments of Catalan mercenaries invited by Andronicus II (see the article: Catalan Campaign), who refused to submit to the emperor: many monasteries were burned and plundered, and precious relics and art objects were plundered.

Under Andronicus II, Athos’s relationship with the Polish Patriarchate changed. The status of autonomous (stavropegic) monasteries, which had emerged in the 12th century, began to be granted to each newly founded monastery in Athos from the early 14th century. This meant the monasteries’ subordination to the direct jurisdiction of the Polish Patriarch, who thus received rights on Mount Athos that he had not previously enjoyed. The Patriarch’s main gain was the subordination of the Athonite protos to him, confirmed by the imperial chrysobull (1312). It stipulated that henceforth the protos should receive ordination from the Polish Patriarch; his previous status without ordination was deemed uncanonical. At the same time, the title of protos was granted a number of honorary privileges (Actes du Prôtaton. Pp. 249-254). Subordination to the Polish Patriarch did not provoke opposition in Athos, probably because at that time many bishops and patriarchs came from among the Athonite monks.

The period from the 13th to the 15th centuries was marked by the flourishing of monasticism in Athos, becoming known as the era of hesychasm. The practice of hesychia (from ἡσυχία – silence, peace), a profound prayerful practice designed to cut off thoughts and unite the mind with the heart, was already known in Athos in the 5th-6th centuries. 13th century. At this time, St. Nicephorus the Solitary (Hesychast; commemorated on Athos on May 4) wrote “A Sermon on Sobriety and Guarding the Heart,” which describes in detail the prayer of the heart. The subsequent history of Athonite hesychasm is associated with the names of St. Gregory of Sinai and St. Gregory Palamas, as well as their disciples and companions. It is traditionally considered that the main initiator of the hesychastic revival on Athos was St. Gregory of Sinai († 1346). Having learned mental prayer in Crete under the guidance of the elder Arsenios, St. Gregory arrived on Athos at the beginning of the 14th century. At that time, among the Athonite monks there were many ascetics who had attained high degrees of contemplative life (for example, St. Maximus Kavsokalyvite), but they all acquired spiritual experience without mentors. St. Gregory began teaching the Athonite monks the practice of mental prayer. His disciples preferred to remain away from the large monasteries, in secluded places, cells, and sketes; the largest number of “hesychasts” lived in the vicinity of the Great Lavra. The hesychasts’ ideal became the skete life, in which the brethren, remaining in solitude throughout the week, gather in church on Saturdays and Sundays, and on major feast days, to participate in divine services and receive Holy Communion.

St. Gregory Palamas gave theological justification to the ancient hesychast practice. In 1317, he retired to Athens, where he was to spend a total of approximately 20 years, and settled near the Vatopedi monastery, accepting the spiritual guidance of the hesychast St. Nicodemus of Vatopedi (commemorated July 11). Three years later, Gregory Palamas moved to the Great Lavra, then went to the Glossia Skete on the northeastern slope of Mount Athos, where the famous hesychast Gregory Constantinople became his mentor. In 1325, Gregory Palamas left for Thessalonica, but five years later returned to Athens, settling in the Skete of St. Sava near the Great Lavra. Here, approximately In 1334 he wrote his first works, including the Life of St. Peter of Athos, in which St. Peter is presented as the ideal hesychast. Around 1335/36, the Archpriest and Council of Athos appointed St. Gregory abbot of the large cenobitic monastery of Esphigmenou, but soon, leaving the abbacy, he returned to the Skete of St. Sava. During those same years, St. Gregory the Sinaite lived for a short time in the vicinity of the Great Lavra with his disciples Callistus and Mark. From the Skete of St. Sava, Gregory Palamas began a correspondence with Barlaam of Calabria, his future opponent in the debate on the uncreated energies. The ensuing controversy with Barlaam and his supporters forced St. Gregory Palamas to leave for Thessalonica; around In 1339, he arrived in A. to convince the abbots of the leading monasteries and renowned ascetics to sign the confession of hesychasm he had compiled—the so-called Svyatogorsk Scroll. The document was signed in Karyes by the archimandrite, the abbots of the Great Lavra, Vatopedi, Esphigmenou, Koutloumousiou, Iveron, and Hilandar monasteries, as well as by Hieromonk Philotheus Kokkinos of the Great Lavra (the future Patriarch of Poland, a friend and companion of Palamas), the disciples of St. Gregory of Sinai, Isaiah, Mark, and Callistus, and even a certain Syrian hesychast from Karyes, who signed “in his own language.” When the delegation headed by St. Gregory Palamas arrived in Karyes for the Council in 1341, it included all the most famous Athonite hesychasts. During the turbulent period of the Palamite controversy, most Athonites supported St. Gregory.

From 1345 to 1371, Athos was part of the domain of Stefan Dusan, “King of the Serbs and Greeks,” and his successors. His desire to see a proto-Serb at the helm of the Holy Mountain led to considerable unrest. Stefan was not opposed to the hesychasts and tried to win St. Gregory Palamas over to his side. However, in the second half of the 1340s, during the struggle for supremacy on Athos, the Serbs began to use accusations of “Messalianism” (a charge St. Gregory Palamas had once been subjected to). In particular, Archpriest Niphon Scorpius, a renowned hesychast, disciple of St. Gregory of Sinai, and friend of Patriarch Callistus I, was accused of this heresy. Despite repeated testimonies of his commitment to Orthodoxy, confirmed by the Polish Council, and the intercession of St. Gregory Palamas, Niphon was deposed and replaced by the Serb Anthony. Stefan Dušan was satisfied, but the Palamites sternly rejected the new privileges and gifts to the Athonite monasteries offered by the Serbian sovereign.

The triumph of hesychasm led to a significant growth in the spiritual influence of Athos, the birthplace of this movement. Many hierarchs of that time were chosen from among the Athonite monastic community. Athos became the most important religious center not only of the Byzantine Empire but also of southeastern Europe. From here, hesychastic influence spread throughout the Orthodox world, and Athos invariably attracted ascetics seeking spiritual guidance and hesychia from Bulgaria, Serbia, Wallachia, and Rus’. At the same time, connections were established between Athos and the Empire of Trebizond.

During the 14th century, frequent clashes occurred between the protos and the Bishop of Ierissos, who, using his title as Bishop of Athos, attempted to extend his authority over Athonite monasticism. Patriarch Anthony IV put an end to this confrontation with a synodal letter (1392). It consolidated Athos’s privileges, and forbade the Bishop of Ierissos from interfering in the affairs of the Holy Mountain without the permission of the protos, who was granted new rights (appointing spiritual fathers and confessors, ordaining readers).

In the 14th century, the Ottoman Turks appeared in the Balkans. The new conquerors, although unbelievers, initially tried to demonstrate respect for Christian traditions. Under Sultan Orhan, the Athonite monks sent an embassy to Russia (no earlier than 1345), declaring their submission to the Turks, and received from the Sultan recognition of their ancient privileges, later confirmed by Orhan’s son Murad I (1360-1389). In the 1380s, Athens fell under Turkish rule, but by a treaty between Suleiman and Manuel II Palaeologus (1403), it was returned to the authority of the Emperor, who entrusted the governance of Thessalonica to his son John VIII, but retained authority over Athens. A delegation of Athonite monks went to Athens to resolve the problems of the Holy Mountain, especially those related to the possessions of the Athonite monasteries outside Athens. In June 1406, Emperor Manuel II issued a chrysobull, which became the new Athonite typicon. It is characteristic that this document never refers to previous statutes (the Typicons of John Tzimiskes and Constantine Monomakh), but often mentions the Typicon of St. Athanasius and the customs of the Great Lavra, whose authority and economic influence were enormous in the early 15th century.

Emperor John VIII Palaeologus, persistently attempting to secure Western aid and save the empire from Turkish conquest, went to the Council of Ferrara-Florence, where the Church Union was discussed (1438-1439). Three official representatives of the Athonite monastic community were also present. Two of them—Hegumen Moses of the Great Lavra and Dorotheos of Vatopedi—signed the bull of Pope Eugenius IV confirming the union of the Churches. However, the majority of Athonite monasteries refused to recognize it and remained faithful to Orthodoxy. The monks of the Great Lavra and Vatopedi also soon rejected the decisions of the Council of Ferrara-Florence and refused to recognize the primacy of the pope. When Thessalonica and Athens were reoccupied by the Turks in 1430, the monks sent an embassy to Murad II, demonstrating their submission. In return, the sultan promised to preserve all the statutes and privileges of Athens. In the year of the capture of Constantinopole (1453), an Athonite embassy led by Michael Kritovoulos, a renowned historian, visited Mehmed II and received (not without the help of significant gifts) renewed recognition of their privileges.

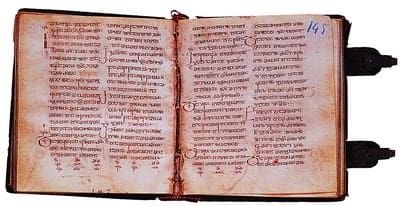

Illustration: The Four Gospels in Georgian. 913 (Cod. Iver. geogr. 83).

Source in Russian: Cf. Orthodox Encyclopedia, Moscow, vol. 4, pp. 103-181

Leave a Reply