During the Ottoman era, Athos remained under the patronage (though not always unselfish) of the Turkish sultans, which allowed the Holy Mountain to retain at least some of its former glory. The Athonite community had its own representatives in the Turkish administration: one in Thessalonica and two in the city (under the Patriarch and the Sublime Porte). Athos enjoyed relative independence and served as a kind of oasis for Christians, where the oppressed sought refuge, seeking silence and asceticism to forget their enslavement. Athos remained completely isolated from the rest of the world, and only distant echoes of historical events reached these places. The monks lived in peace, disinterested in politics, thereby protecting themselves from the arbitrary actions of the Turks. During Turkish rule, monastic life was primarily focused on the monastic life. In 19 monasteries, to which the monastery of Stavronikita was added in 1541/42 (for the number of brethren of individual monasteries and of Athos as a whole from the late 15th to the second half of the 18th century, see: Fotiћ. pp. 98-99). Thus, the group of 20 main monasteries that still exists today was formed, among which the entire area of Mount Athos was divided, and no one except them could henceforth own land on Athos.

In 1513, Sultan Selim I was solemnly received at Mount Athos (the warriors accompanying him were engaged in plunder). The Sultan issued a firman concerning the Xeropotamou Monastery and confirmed the privileges of Mount Athos. The same was later done by Sultans Ahmed III, Selim III, Mahmud II, and others. Islamic law prohibited the construction and restoration of Christian buildings, but such permission was granted to A. without difficulty. However, the Turks were not always and not in all respects benevolent. A very high poll tax (kharaj) was imposed on all inhabitants of the Holy Mountain, the amount and method of collection of which were determined by Sultan’s firmans, Patriarchal sigillia, and other documents. Despite individual tax concessions granted by the Sultans, the annual collection of this sum became increasingly difficult (see: Fotiћ. pp. 63-78). The monasteries were also repeatedly subjected to unbearable additional taxes and levies, and monastic farmsteads and estates outside of Athos were frequently confiscated.

Continued pirate raids, internal strife, and Turkish arbitrary rule had tragic consequences: many monasteries fell into decline and could have disappeared without outside support. It became clear that it was impossible to maintain life in the monasteries solely through land cultivation. Part of the expenses were covered by donations and alms collected by monks sent to all corners of the Orthodox world. Thanks to these gifts, the monastic community of Athos not only survived but was also enriched with venerated relics and holy relics, sacred vessels, and precious vestments. The rebuilding and restoration of the monasteries contributed to the flourishing of art in Athos.

From the second half of the 15th century, the main donors were Orthodox Christians. The rulers of the Wallachian and Moldavian principalities (see the section “Athos and the Romanian Principalities”). After official relations were established between Athos and the Moscow grand princes and metropolitans in the late 15th century, embassies from Athonite monasteries regularly visited Russia to collect financial aid for the Holy Mountain (see the section “Athos and Russia”). Despite the generous donations of Orthodox sovereigns, the monasteries continued to exist in poverty due to crushing debts. Estates in the Danubian countries yielded little income due to communication difficulties and the unstable political situation; monks’ journeys to Russia to raise funds did little to alleviate the general impoverishment.

Patriarch of Constantinopole Jeremiah II attempted to organize the life of the Athonite monasteries. Arriving in Thessalonica, he convened the Athonite fathers to discuss the problems of the Holy Mountain. In 1573, Patriarch Sylvester of Alexandria was sent to Athos. He examined the state of affairs on the spot and compiled a new Athonite typicon, which was approved by the sigillium of the Polish Patriarch in 1574/75 (Meyer. Haupturkunden. 1894. pp. 215-218). The monks were forbidden to go beyond the boundaries of Mount Athos to settle internal disputes; everything had to be resolved on the spot, peacefully and in accordance with church custom; it was forbidden to sow wheat or barley on Mount Athos, only legumes were allowed to be grown; the collection of nuts for sale outside of Athos and the trade in monastic vestments were prohibited; fixed internal prices were established for nuts, cherries and vegetable oil; the presence of children, beardless youths and wives’ animals was strictly prohibited on Mount Athos. sex, as well as the residence of Athonite monks in courtyards outside of Athos together with the “sisters”; laymen who had lived in Athos for 3 years were ordered to be tonsured as monks or expelled; celliot monks were forbidden to leave Athos to collect alms; not only the production and consumption of grape vodka (rakia) was prohibited, but even the cultivation of vineyards (with the exception of a few table grape vines) in the sketes. However, these measures only partially achieved their goal.

When the former Patriarch Anthimos II of Constantinopole visited the Great Lavra (1623), he found only five monks living in poverty, a situation that neither the return to the communal rule initiated by Jeremiah II nor the gifts received helped alleviate. Only from 1630 did this famous monastery gradually begin to recover, especially after Patriarch Dionysius III (1665) found refuge there, donating his personal property to the monastery. The 17th century saw a sharp economic decline and the abandonment of many Athonite monasteries (Xenophon, Rusicus, Kastamonita, and others). Only a few monasteries enjoyed relatively prosperous conditions, such as Iveron (in the 17th century, 300 monks lived within the monastery itself and 100 outside it), Hilandar, Vatopedi, and especially the monastery of St. Dionysios, known for its particularly strict rule, which took fifth place in the list of Athonite monasteries, displacing Xeropotamou.

In the 16th century, some monasteries returned to the ancient cenobitic rule (Great Lavra, Vatopedi), but throughout the 17th century, monasteries one after another began to transition to idiorrhythmia, and by 1784, all Athonite monasteries had become solitary. Another feature of this era, which may have been a reaction to the widespread practice of solitary life, was the emergence of sketes, which began in the second half of the 16th century. In ancient times, the word “skete” was synonymous with the word “lavra”; the Athonite skete consisted of several houses or huts where monks lived, and was similar to a village; in the center was a common church – kyriakon. The difference from the ancient lavra was that the sketes were dependent on the mon-rei. The community of skete hermits was governed by a dikeios (δικαῖος, from δίκαιος – fair) with several assistants. The appearance of sketes may have reflected the opposition of strict ascetics to the spread of idiorrhythmia, which they considered a deviation from ancient traditions and a sign of decline and secularism. The first to be founded was the skete of St. Anna, which belonged to the Great Lavra (1572). The Kavsokalyvia skete was founded by St. Akakios the New Kavsokalyvites († 1730), renowned for his particularly rigorous asceticism. In the 16th and 17th centuries, other large sketes emerged: St. Demetrius (Vatopaidi), St. John the Baptist (Iveron Monastery), St. Panteleimon (Koutloumousiou), the New Skete of the Mother of God and the Romanian Skete of St. Demetrius (Monastery of St. Paul), Annunciation of the Mother of God (Xenophon), and Prophet Elijah (Pantocrator).

During the 18th century, large debts continued to burden the monasteries, and the economic situation of most remained dire; the monks’ constant concern for material needs affected their spiritual life. This situation necessitated reforms. In 1783, Patriarch Gabriel IV issued a new typicon for Mount Athos (Meyer. Haupturkunden. 1894. pp. 243-248). Its main goal was to restore the ancient customs of austere monastic life, which had long since ceased to be observed. Eating meat was prohibited, as was leaving Mount Athos without permission, and leaving the monastery for a skete. The number of laypeople living in Karyes was limited. The position of protos, abolished since 1585, was restored, and four co-rulers were added to him, elected from among the monks of 20 monasteries. The thus-formed Priestly Epistasy (guardianship) assumed responsibility for overseeing the lives and conduct of the monks. The protos was elected for life and received ordination from the Patriarch. He kept the keys to the assembly hall, and each epistate received a quarter of the seal of the Holy Mountain. Measures were also taken to liquidate debts. One of the most important results of Gabriel IV’s reforms was the gradual return to communal life. The monasteries of Xenophon (1784), Esphigmenou (1796), Simonopetra (1801), St. Panteleimon (1803), St. Dionysios (1803), Karakalp (1813), Kastamonitou (1818), and St. Paul (1839) adopted the coenobium charter, soon followed by the monasteries of St. Gregory, Zograf, and Koutloumousiou.

17th-18th centuries

Over the course of several centuries of Turkish rule, the culture and education of the Greek people gradually declined, which could not but affect A. Mn. Monks began to abandon the large communal monasteries, moving to sketes, which gradually became large monastic communities reminiscent of the ancient lavras of Egypt, Syria, and Palestine. In the large monasteries, fewer and fewer monks remained to care for the monasteries’ book treasures, and the copying of manuscripts practically ceased.

In the early 17th century, the Jesuits attempted to expand their activities in Karyes, seeking to persuade the Athonite ascetics to accept the Union. Pope Gregory XV sent the Uniates Anthony Vasilopoulos and Kanakios Rossis to Karyes, who managed to organize a school in Karyes, which operated from 1636 to 1641. Nicholas Rossis directed the school, and about 20 monks attended it. In 1641, at the request of the Polish Patriarch, the Turkish authorities forced the Jesuits to close the school and leave Karyes. The school was moved to Thessalonica.

Despite the general cultural decline, Athonite literature did not cease to exist during these difficult centuries. At the beginning of the 17th century, Hieromonk Hierotheus continued compiling the “Tale of the Iveron Monastery,” begun in the 16th century by Theodosius. At the end of the 17th century, Hieromonk Gregory of Kastamonitou Monastery wrote “Notes on the Founding of this Monastery and monastic life on Athos.” Agapius Land took monastic vows on Mount Athos and lived for about two years in the vicinity of the Great Lavra, where he completed a significant portion of his translations of the lives of saints into the vernacular Greek language.

In the 18th century, spiritual life in Athos was revived by the founding of theological schools and the strengthening of cultural contacts with the West and Slavic countries. The Athonite monk Hierotheos Ivirit (1686-1745) studied and translated into vernacular Greek the works of St. Ephraim the Syrian and the lives of the saints. Hierotheos’s disciple was Caesarius Dapontis, whose life was also closely connected with Athos. In 1757, already a monk, he came to the Xeropotamou Monastery and that same year was sent to collect alms for the monastery. After many years of wandering, he returned to Athos in 1765 and lived in Xeropotamou for 20 years, where he wrote his major works.

In the mid-18th century, the Athonite Academy, or Athoniada, was founded (see below). For a time, it was headed by the famous Eugenius (Bulgaris). Bulgaris’s disciple, Cosmas of Aetolia, did much in the field of spiritual education. In 1742, he came to Aetolia and took monastic vows at the Philotheos Monastery. From 1760, he served as a preacher, first in the vicinity of K-Polu, then on the Greek islands, founding 10 large schools and approximately 200 public schools.

In 1754, a dispute arose in Aetolia regarding the commemoration of the dead. The cell monks of St. Anne’s Skete, who were working on the construction of their cathedral church (katholikon), could only perform memorial services on Sundays. This provoked discontent among other monks, who saw this as a violation of the tradition, also common in Aetolia, of commemorating the dead on Saturday. The dispute resulted in discord and unrest, affecting all the sketes and monasteries of the Holy Mountain. Those who supported the “Saturday” commemoration (among them Neophytos Kavsokalyvites, Athanasios of Paros, Christopher of Arta, Agapios the Cypriot, Jacob of the Peloponnese, and the hermit Paisios) began to be called Savvatians (Saturday-keepers) or Kollyvadians. The Patriarchs of Constantinopole repeatedly attempted to intervene in the conflict and resolve all disputes. Thus, Patriarch Sophronius issued a decree condemning Athanasios, Jacob, Agapios, and Christopher, decreeing that the commemoration of the dead could be performed on any day of the week (1776). Athanasios of Paros was forced to write a letter of “justification,” officially accepted in 1781 by Patriarch Gabriel. At the same time, the question of how often one should receive Holy Communion was actively debated on Athos. Patriarch Theodosius decreed in a 1772 decree: “No precise time should be determined, but preliminary preparation through repentance and confession is undoubtedly necessary.” Athanasius of Paros, in his work “Exposition, or Confession of the True and Orthodox Faith,” emphasized that one should not receive Divine Communion every day, but rather that one must first repent of one’s sins and confess. In 1785, Patriarch Gabriel, under threat of excommunication, forbade the Athonite monks from receiving Communion too frequently. However, in 1789 and 1794, Patriarch Neophytos rescinded this decree of his predecessor, and Gregory V, in a decree of 1819, decreed that Communion should be received on Sundays.

One of the most prominent representatives of Athonite spiritual life during this period was St. Nicodemus of the Holy Mountain. In 1775, at the age of 26, he came to the Holy Mountain and settled in the Monastery of Dionysios, where two years later he was tonsured a monk. Having studied the manuscript treasures of the monastery, at the request of St. Macarius, he prepared the Philokalia for publication, checking and supplementing the text based on various manuscripts (1782). St. Nikodim also published the Collection of Divinely Prophecied Words and Teachings of the God-Bearing Holy Fathers and the work of Neophytos Kavsokalyvite On Frequent Divine Communion. Many works of the Holy Fathers were translated by him into the vernacular Greek. St. Nikodim authored a collection of canons dedicated to the Mother of God (Theotokarion – Theotokion), and he translated and published the treatise “Invisible Warfare,” which detailed the practice of spiritual life. In the debates over the day of commemoration of the dead, Nikodim supported the Kollyvades and, in his treatise “Apology of Faith,” insisted on adhering to the ancient tradition and commemorating the dead on Saturdays. This work, published only in 1819, led to the issuance of a decree by Patriarch Gregory V, confirming and reiterating his 1807 decree on the permissibility of commemoration on any day. St. Nikodim died on the Holy Mountain. In 1955, at the initiative of the Athonite monks, the Patriarchate of Constantinopole canonized him.

In the 18th century, monastic interest in the history of Mount Athos grew. In the mid-century, Macarius Trigonis of the Great Lavra compiled the “Proskynitarion of the Lavra”; around the same time, Monk Euthymius wrote the verse “Proskynitarion of the Lavra” and the Life of St. Athanasius the Athonite. Jacob of the Gregory Monastery translated first into Wallachian and then into modern Greek the description of this monastery, written in the 1720s by the Russian pilgrim V.G. Grigorovich-Barsky. Theodoret, abbot of the Esphigmenou Monastery, wrote a history of his monastery.

Many prominent hierarchs of that era (including several Patriarchs) retired to Mount Athos. A. visited Mount Athos more than once. Makariy Notara (1731-1805), who rallied the Peloponnesian Greeks to fight against the Turkish yoke during the Russo-Turkish War under Catherine II. The spiritual upsurge in Athos could not help but affect monks of non-Greek origin. Venerable Paisius of Hilandar compiled the first history of the Bulgarian people in the mid-18th century, which was widely disseminated in Bulgaria. The Romanian monk Philotheus of Athos translated “Christian Teachings” and “The Flower of the Muses” into Romanian. Many students of the Athonite Academy spread their knowledge in Moldova and Wallachia. The spread of Athonite spiritual practice in Russia is associated with the name of Venerable Paisius (Velichkovsky).

19th century

In the early 19th century, the situation at Mount Athos improved. Donations increased, debts were paid, and the number of sketes grew. All monasteries, especially Velichkovsky, The Lavra, Vatopedi, and Iveron, experienced a period of prosperity thanks to significant income received from their holdings in Chalkidiki, the islands of the Aegean, Asia Minor, Macedonia, Thrace, Romania, and Russia. In 1810, a new charter was adopted, approved by the Turkish governor in Thessaloniki (Meyer. Haupturkunden. 1894. pp. 603-604). The Holy Community became the governing body of the monastic community of Athos, and the Holy Epistasion became the supervisory body. The office of protos was finally abolished. The return to the cenobitic charter led to moral and spiritual flourishing.

After the outbreak of the Greek revolt (1821), the Holy Mountain suffered new great hardships. During the period of Turkish rule, the Athonites avoided interfering in politics, not wishing to incur the wrath of their oppressors. However, at the end of In the 18th century, after Patriarch Seraphim II, who had been exiled there, fled from Athos to take refuge in Russia, which was hostile to the Turks, Athos drew the suspicion of the Ottoman authorities. The threat of occupation arose, but was averted at the last moment thanks to the mediation of Patriarch Theodosius in exchange for an increase in tax collection.

During the Greek national liberation movement of the 1820s, some monks joined the rebels. In April 1821, Emmanuel Pappas, the leader of the Macedonian rebels, landed on Athos, gathering a number of monks (especially young people), and raising the banner of armed struggle against the Turks. In retaliation, the Ottoman authorities began arresting and subjecting Athos monks living outside Athos to horrific torture. The presence of 5,000 refugees, women, and children on Athos also created numerous problems. Pappas’s detachment suffered a defeat in Chalkidiki, but the monks, retreating to Ankara, organized a defense of the peninsula on the isthmus. The Thessaloniki Pasha, Abdul Abut, offered the monks amnesty in exchange for the surrender of Pappas, who had taken refuge in Ankara, but he fled to Hydra and died en route. On December 15, 1821, the pasha, at the head of an army of 3,000 Kurds, occupied Ankara, imposed a huge indemnity on the monastery, demanded the surrender of their weapons, and the surrender of the Athonite abbots as hostages. The following year, he left a well-armed garrison in each monastery and sailed with the hostages to Cyprus. Turkish detachments remained in Ankara until 1830, and this time marked the present for Mount Athos. A disaster: the invaders tortured and killed monks, plundered monasteries and churches, burned the Athonite printing house in the Great Lavra, and burned many manuscripts for kindling. The presence of garrisons led to the evacuation of many monasteries, and the number of monks on Mount Athos dropped to 2,500. From 1869, Mount Athos was governed by a Turkish kaymakam, whose residence was in Karyes. It reported to the Turkish financial department and had very limited powers, primarily responsible for tax collection and police functions.

The rise of national consciousness among Greek and other Orthodox peoples in the 19th century resulted in attempts to involve Mount Athos in interethnic conflicts. Since ancient times, Serbs, Romanians, Bulgarians, Russians, and Georgians have lived alongside the Greeks in Armenia. Greek monks traditionally constituted the overwhelming majority, and with the emergence of the Greek state, many of them felt their involvement in the cause of pan-Greek political and spiritual revival. Along with this, during the 19th century, interest in Armenia from Russia, the most powerful Orthodox power, significantly increased. Despite the opposition of some Greek monasteries, the number of Russian monks in Armenia grew rapidly, which was facilitated by generous material and diplomatic support from Russia. Under the patronage of the imperial house, the construction of Russian sketes of St. Andrew the First-Called and the Prophet Elijah proceeded on an unprecedented scale, but the main center of the Russian presence at the monastery of St. Panteleimon, which had long been known as the Russian Monastery, became the center of the monastery on Mount Athos. If at the beginning of the 19th century there were practically no Russian monks here, then by 1874 there were 300 Russians for every 200 Greeks in the monastery; a Russian abbot, Makarii, was elected for the first time (1875), and the number of monks was constantly increasing. Despite the fact that at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries the Polish Patriarchate and the Turkish government began to pursue a policy of restraining “Russian expansion”, by 1912 Russian monks constituted half of the population of Mount Athos. In 1913 their number sharply decreased as a result of the deportation of more than 800 adherents of the name-worshipper movement from Athos. The revolution of 1917 and subsequent events led to the cessation of the influx of monks from Russia.

Athos after 1912

At the beginning of the First Balkan War (1912-1913), a service for the victory of Greek arms was held in the Protaton Church. When the Greek cruiser Averof, escorted by several destroyers, approached Athos and the flag of the Orthodox state—the Kingdom of Greece—was raised over the summit of Mount Athos, the event was greeted with the solemn ringing of thousands of bells from the churches of Athos (November 2, 1912). Centuries of Turkish rule had ended.

The London Peace Conference of Ambassadors (1913) confirmed, in the form of a temporary resolution, Athos’s status as an autonomous and independent monastic state under the joint protectorate of the Balkan Orthodox powers. However, according to one of the articles of the Treaty of Sèvres (1920), confirmed in 1923 in Lausanne, Athens was officially recognized as part of Greece. Under this agreement, the Greek authorities formally guaranteed immunity to monks of non-Greek origin. In 1924, the “Statutory Charter” of Mount Athos was developed, which still governs the governance of Athens.

The Greek government made efforts to restore Athens’ financial situation, which had sharply worsened after the cessation of revenues from the Athonite monasteries’ holdings in Russia and the state’s confiscation of Athonite metochions in Greece and abroad in favor of Greeks expelled from Turkey after the so-called Asia Minor catastrophe of 1923. For the same purpose, the Greek authorities purchased part of Athens’ territory between the Xerxes Canal and Ouranoupolis.

During World War II, Athens, along with all of Greece, was destroyed. The people endured the hardships of occupation. In the post-war years, Greece was engulfed in civil war, and Athos sheltered numerous refugees, which caused significant damage to the monasteries of the Holy Mountain. It was then that women served as partisans on Athos for the last time. At the same time, the governments of Poland, Bulgaria, Romania, and Yugoslavia confiscated Athonite estates within their countries, further worsening Athos’s economic situation.

The number of Athos monks steadily declined until the 1970s. In 1971, a minimum of 1,145 was recorded; in 1972, their number increased for the first time, which was perceived as a significant event. Since then, the number of Athonite monastics has grown steadily, increasing by approximately 30 monks per year. Currently, the Hagiorites are international; in addition to Slavs, they include immigrants from Western Europe, America, and Australia. In 1981, the Center for the Protection of Athonite Heritage (Κέντρο Δυαφύλαξης ῾Αγιορειτικῆς Κληρονομίας – ΚεΔΑΚ) was established under the Greek government, which took under its control the registration and preservation of Athonite valuables, as well as new construction on Athos. The European Community provides significant financial support for the restoration of Athonite monuments, which, however, raises concerns among some elders about the inevitable indirect compensation in the future (for example, by allowing women’s pilgrimages to Athos). At present, the Greek government has succeeded in concluding unification European agreements to defend the unique structure of Athos. A key event was the exhibition “Treasures of the Holy Mountain” in Thessaloniki in 1997. The exhibition featured numerous monuments of Athonite heritage, most of which were leaving Athos for the first time.

History: Meyer Ph. Die Haupturkunden für die Geschichte der Athosklöster. Lpz., 1894; Афонский Патерик. М., 1897, 1994р; Millet G., Pargoire J., Petit L. Recueil des inscriptions chrétiennes du Mont Athos. P., 1904; Billetta R. Der heilige Berg Athos in Zeugnissen aus 7. Jh. W.; N. Y.; Dublin, 1992-1996. 4 Bde. Акты: Actes de Chilandar / Publ. par L. Petit et B. Korablev // ВВ. 1911. Т. 17. Прилож. I-III. C. 1-368; 1915. Т. 19. Прилож. I. С. 369-651; То же. Amst., 1975r; Actes de Chilandar: Des origines à 1319: [Texte. Album] / Ed. M. Živojinović, Ch. Giros, V. Kravari. P., 1998. (Archives d’Athos [далее AA]; 20); Actes de Dionysiou / Ed. N. Oikonomidиs. P., 1968. (AA; 4); Actes de Docheiariou: [Texte. Album] / Ed. N. Oikonomidès. P., 1984. (AA; 13); Actes d’Esphigménou / Ed. L. Petit, W. Regel // ВВ. 1907. Т. 13. Прилож. I. C. 1-123; Actes d’Esphigménou / Ed. J. Lefort, 1973. (AA; 6); Actes d’Iviron. T. 1: Des origines au milieu du XIe siècle / Ed. J. Lefort, N. Oikonomidès, D. Papachryssanthou, avec la collab. d’H. Métrévéli. P., 1985; T. 2: Du milieu du XIe siècle à 1204. 1990; T. 3: De 1204 à 1328. 1994; T. 4: De 1328 au début du XVIe siècle. 1995. (AA; 14, 16, 18, 19); Actes de Kastamonitou / Ed. N. Oikonomidès. P., 1978. (AA; 9); Actes de Kutlumus / Ed. P. Lemerle. P., 1945, 19882. (AA; 2); Actes de Lavra: 897-1178 / Ed. G. Rouillard, P. Collomp. P., 1937. (AA; 1); Actes de Lavra. Pt. 1: Des origines à 1204: [Texte. Album] / Ed. P. Lemerle, A. Guillou, N. Svoronos, D. Papachryssanthou. P., 1970; Pt. 2: De 1204 à 1328: [Texte. Album]. 1977; Pt. 3: De 1329 à 1500: [Texte. Album]. 1979; Pt. 4: Études historiques. Actes serbes: [Texte et planches] / Avec la collab. de S. Ćirković. 1982. (AA; 5, 8, 10, 11); Actes du Pantocrator / Ed. L. Petit // ВВ. 1906. Т. 12. Прилож.; Actes du Pantocrator: [Texte. Album] / Ed. V. Kravari. P., 1991. (AA; 17); Actes de Philothée / Ed. W. Regel, E. Kurtz, B. Korablev // ВВ. 1914. T. 20. Прилож.; Actes du Prôtaton: [Texte. Album] / Ed. D. Papachryssanthou. P., 1975. (AA; 7); Actes de Saint-Pantéléèmôn: [Texte. Album] / Ed. P. Lemerle, G. Dagron, S. Ćirković, 1982. (AA; 12); Actes de Xénophon / Ed. L. Petit // ВВ. 1903. Т. 10; То же. Amst., 1964; Actes de Xénophon: [Texte. Album] / Ed. D. Papachryssanthou. P., 1986. (AA; 15); Actes de Xéropotamou / Ed. J. Bompaire. P., 1964. (AA; 3); Actes de Zographou / Ed. L. Petit, W. Regel // ВВ. 1911. T. 17. Прилож.; Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents / Ed. J. Thomas, A. Constantinides Hero. Wash., 1998 (= http://www.doaks.org/typ000.html).

Literature: Порфирий (Успенский), еп. Первое путешествие в афонские монастыри и скиты. К., 1877. Ч. 1-2; он же. Второе путешествие по Святой Горе Афонской. М., 1880; он же. История Афона. К., 1877. Ч. 1-3/1; СПб., 1892. Ч. 3/2; Γεδεών Μ. ῾Ο ̀Αθως. ̓Αναμνήσεις, ἔγγραφα, σημειώσιες. Κωνσταντινούπολις, 1885; Петрушевский П. Святые места и святыни на Востоке и в России. СПб., 1902; Вышний покров над Афоном. М., 19029; Γεράσιμος ̓Εσφιγμενίτης (Σμυρνάκης), μον. Τὸ ̀Αγιον ̀Ορος. ̓Αθῆναι, 1903. Καρυαί, 19882; Κοσμὰς ῾Αγιωρείτης (Βλάχος), μον. ῾Η χερσόνησος τοῦ ῾Αγίου ̀Ορους ̀Αθω καὶ αἱ ἐν αὐτῷ Μοναὶ καὶ οἱ Μοναχοὶ πάλαι τε καὶ νῦν. Βόλος, 1903; Lake K. The Early Days of Monasticism on Mount Athos. Oxf., 1909; Χριστόφορος (Κτενᾶς), ἀρχιμ. ̀λδβλθυοτεΑπαντα τὰ ἐν ῾Αγίῳ ̀Ορει ἱερὰ καθιδρύματα εἰς 726 ἐν ὅλῳ ἀνερχόμενα, καὶ αἱ πρὸς τὸ δοῦλον ἔθνος ὑπηρεσίαι αὐτῶν. ̓Αθῆναι, 1935; Dölger F. Aus den Schatzkammern des Heiligen Berges. Münch., 1943; idem. Mönchsland Athos. Münch., 1943; Dölger F., Weigand E., Deindl A. Mönchsland Athos. Münch., 1943; Hofmann G. Rom und der Athos. R., 1954; Amand de Mendieta E. La presqu’île des caloyers: Le Mont-Athos. Bruges; P., 1955; idem. Mount Athos. B.; Amst., 1972; Darrouzès J. Une république de moines. P., 1956; Dahm Chr., Bernhard L. Athos: Berg der Verklärung. Offenburg, 1959; Sherrard Ph. Athos: der Berg des Schweigens. Olten, 1959; idem. Athos: the Mountain of Silence. L., 1960; ̓Αλέξανδρος Λαυριώτης (Λαζαρίδης), μον. ῾Ο ̀Αθος̇ ̓Αγῶνες καὶ θυσίαι (1850-1855)̇ ̓Εγγραφα Μακεδονικῆς ̓Επαναστάσεως. ̓Αθῆναι, 1962; Millénaire du Mont Athos. Chevetogne, 1963-1964. 2 vol.; Huber R. Athos. Zürich, 1969; Μαμαλάκης Ι. Π. Τὸ ̀λδβλθυοτεΑγιον ̀ρδβλθυοτεΟρος διὰ μέσου τῶν αἰώνων. Θεσσαλονίκη, 1972; Карпов С. П. Трапезундская империя и Афон // BB. 1984. T. 45. C. 95-101; Nastase D. Les débuts de la communauté œcumenique du Mont Athos // Σύμμεικτα. 1985. T. 6. Σ. 251-317; Wittig A. M. Der Heilige Berg von Byzanz. Würzburg, 1985; Δωρόθεος, μον. Τό ̀λδβλθυοτεΑγιο ̀ρδβλθυοτεΟρος. Κατερίνη, [1986]; Χρήστου Π. Τὸ ̀Αγιον ̀Ορος̇ ̓Αθωνικὴ πολιτεία – ἱστορία, τέχνη, ζωή. ̓Αθήνα, 1987; Παπαχρυσάνθου Δ. ̓Ο ἀθωνικὸς μοναχισμός̇ ̓Αρχὲς καὶ ὀργάνωση. ̓Αθῆνα, 1992; Τὸ ̀Αγιον ̀Ορος χθές – σήμερα – αὔριο. Θεσσαλονίκη, 1996; Василий (Кривошеин), архиеп. Афон в духовной жизни православной Церкви // он же. Богословские труды. Н. Новг., 1996. С. 40-68; Mount Athos and Byzantine Monasticism / Ed. A. Bryer, M. L. Cunningham. Aldershot, 1996; Τὸ καθεστὼς τοῦ ̓Αγίου ̀Ορους ̀Αθω. ̀Αγιον ̀Ορος, 1996; ̓Ο ̀Αθως στοὺς 14o-16o αἰῶνες. ̓Αθήνα, 1997; Καβαρνός Κ. Τό ̀Αγιον ̀Ορος. ̓Αθήνα, 2000; Pavlikianov C. The Medieval Aristocracy on Mount Athos. Sofia, 2001; http://www.macedonian-heritage.gr/Athos; http://www.mathra.gr/kedak.

Bibliography in Russian: Prosvirnin A., priest. Mount Athos and the Russian Church: Bibliography. // BT. 1976. T. 15. P. 185-256 [full abstract. decree. rus. publications about A., more than 900 items].

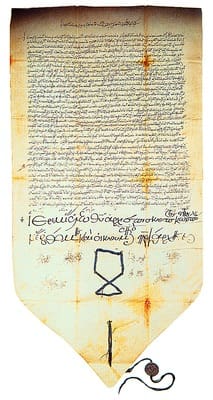

Illustration: Certificate of Patriarch of Constantinople Jeremiah II. 1581 (monastery of Simonopetra)