Organization of Monastic Life

The basic regulations for monastic life are contained in the Athonite Rule; more detailed details are recorded in the internal monastic rules (canonisms). The Rule provides for two forms of monastic organization: cenobitic and solitary. Currently, cenobitic life, dating back to St. Athanasius of Athos, is widespread in all monasteries and many sketes; a number of sketes retain the solitary Rule. In cenobitic monasteries (kinovia), everything is shared: shelter, obediences, meals, and prayer. In solitary monasteries, obediences and food are distributed among individual monks. A cenobitic monastery is governed by an abbot, elected for life by a general meeting of the brethren. All residents at least 40 years of age who have taken monastic vows on Mount Athos and have lived in their monastery or in obedience outside of it for at least 6 years (at St. Paul’s Monastery, at least 15 years) since their tonsure have the right to be elected. The Holy Community and the Patriarchate of Constantinople are notified of the election of an abbot; participation by representatives of the Patriarchate or other bishops in the rite of the abbot’s enthronement is not required. The abbot exercises spiritual authority over the brethren of the monastery, who are obligated to show him respect and complete obedience. The abbot exercises executive authority jointly with a commission (epitropia) of 2-3 epitropes elected for an annual term. Legislative authority is vested in the gerondia (spiritual council), whose number of lifelong members usually ranges from 6 to 12 people. Meetings of the gerondia are held at least once a week. The gerondia makes decisions in cases of disagreement between the abbot and the epitropes. The concentration of all power in the hands of the abbot or his ignoring the rights of the commission or gerondia “is not permitted under any pretext.” The abbot, epitropes, and elders must set an example of communal life, avoid separate meals, teach poverty and love, and personally care for the sick and elderly (Articles 112-122). In solitary monasteries, legislative power was exercised by a meeting of elders elected for life, and executive power was exercised by an annually elected two- or three-member commission (Articles 123-125). Each monastery contains the following books: a) Monkology (Monachologion) – a list of the brethren and information about each monk: lay and monastic name, surname, names of parents, place of birth, occupation before coming to A., time and place of probationary obedience, time of tonsure, property at the time of tonsure, marital status, military service, previous places of asceticism, holy rank (for clergy) and monastic rank (hegumen, counselor, proistamen); b) Book of Novices (Bibeton Dokimoton) – a similar list with information about novices; c) Monachologies of dependent institutions – a list of monks of sketes, cells and other places of asceticism assigned to a given monastery; d) protocol of incoming and outgoing documents; d) the book of deeds of the monastery’s spiritual council; e) the books of administration (Diary; Income and Expenditure; Accounting; Warehouse); g) the ktimatologion (Κτηματολόγιον) – an inventory of the monastery’s real estate; h) the book of records of movable property; i) the book of relics (Βιβλία κειμηλίων) – an inventory of holy relics, sacred vestments and vessels, icons, manuscripts, books, ancient monuments, and all items under the special care of the monastic authorities.

Different monasteries have their own traditions of monastic tonsure. In most monasteries, novices, after undergoing a probationary period of 1 to 3 years, are tonsured into the ryasophore. Rassophore monks may be ordained to the priesthood, which is determined by liturgical needs (usually there are 4-5 hieromonks in a monastery). While fulfilling the obedience of weekly priest, canonarch, and sexton, they wear a mantle, and their names are entered in the monastery’s Monachology. Tonsure into the small schema exists in those few monasteries that do not have tonsure into the rassophore. After a certain period of time (usually about 3 years; in Philotheus Monastery – up to 15 years), rassophore monks or those tonsured into the small schema are tonsured into the great schema. Their name may or may not change. In rare cases, a novice may be immediately tonsured into the great schema. Thus, all Athonite monks sooner or later receive the great schema. All monastic abbots are tonsured into it. Great Schema monks may be ordained to any rank. Tonsures and ordinations are performed by decision of the abbot and the spiritual council; the blessing of the Polish Patriarch is not required for ordination. The schema and polycrest (specially woven rope crosses) are worn under the ryassa only during Holy Communion and when Great Schema hieromonks celebrate the Divine Liturgy.

The monks of each monastery “are obliged to obey their monastic authorities and to unconditionally fulfill the obedience entrusted to them”; in turn, the monastic authorities are obliged “to have paternal love for the monks and impartial and equal care for them all” (Article 92). To be tonsured a monk, a candidate must pass a probationary period of 1 to 3 years and be 18 years of age; a monk tonsured in accordance with this is exempt from military service (Article 93). No one is allowed to leave Mount Athos without written permission from their monastery; a monastery cannot refuse permission for absence to students or persons presenting a valid reason for doing so (Article 96). Each monastery is obliged to maintain a hospital, a pharmacy, and a home for the elderly (Article 102). When elected as monastic superiors (proistamenos), the candidate must be “distinguished by good character, blameless life, and administrative ability, and preference is always given to those with an ecclesiastical and comprehensive education.” During elections, “any interference by the fathers of the monastery, with the exception of the leaders of the assembly, is prohibited.” Superiors are elected for life and are deposed only after a judicial decision has been made. Elections are conducted in accordance with the internal regulations of the monastery (Article 108). At meetings, superiors sit and speak in order of seniority in office; each of them “freely and unrestrictedly expresses his opinion, but always within the bounds of propriety and decorum.” No one may ever be persecuted or punished for censure or controversial opinions (Article 109). Each dependent monastic institution (skete, cell, hesychasterion, kathisma) has its own regulations, approved by the dominant (kyriarchal) monastery. The hermits who labor in these hermitages are considered members of the brethren of the ruling monastery, which grants them possession of their dwelling by executing a so-called debt agreement (ὁμόλογον), drawn up under certain conditions. The person in whose name the agreement is drawn up is called an elder. The kelliotes are subordinate to the elder as abbot. All elders must promptly report on the novices they have accepted as disciples and provide accurate information in their Monachology and Book of Novices. Both of these books are annually reviewed by the ruling monastery. The agreement specifies the names of the brethren who make up the elder’s synody. Alterations are strictly prohibited. When tonsuring a monk or novice, the permission of the ruling monastery is required; only with his consent can a new name be added to the agreement, recognizing the inhabitant as a member of the synody, with the right to legal inheritance. Cells are ceded by the head monasteries at a certain price for the successive ownership of three persons. Kalivas in sketes are acquired after the buyer receives individual permission to purchase from the cathedral of the skete, with the consent of the head monasteries, through the execution of a debt agreement. When selling a cell or kaliva, preference is always given to the head monasteries (Articles 140, 148). Upon the death of the elder of a cell or kaliva, the head monasteries in the agreement “appoint the first person of his synodia in the place of the elder, and the second in the place of the first, also including a third person who has received tonsure with the permission of the monasteries.” The presence of more than six people in one cell or kaliva is prohibited (Articles 159, 162). Those absent without the permission of the head monasteries for more than six months are crossed out of the agreement (Articles 131-132). The internal life of the sketes follows the internal regulations established by the ruling monastery and cannot contradict the current Rule (Article 144). “The monks living in the sketes are obliged to regularly fulfill their religious duties and, without omitting anything, pray at vigils in the temples of the Lord” (Article 145). Each skete is governed by a dikeus (skete leader), advisers (epitropes), and cathedral elders; the dikeus is elected for a term of one year from among the Kalyvite elders, “distinguished by virtues and abilities recognized by the ruling monastery”; half of the 2-4 members of the council are elected simultaneously with the dikeus, the other half are appointed by the ruling monastery. Each skete has its own seal containing its name and the name of the ruling monastery, which consists of several parts kept by the members of the council (Articles 149-154). Movable property on Mount Athos—holy relics, venerated icons, sacred vessels and vestments, precious manuscripts, etc.—is under sacred protection as national treasure and paternal heritage. Each monastery is obligated to maintain a list of sacred relics that constitute its eternal and inalienable property. All immovable property of the monastery is inalienable as a matter of divine right (Article 181). “The sale of land on Mount Athos is under no circumstances permitted, but exchange is possible” (Article 100). All plots of land within the monastery “are leased or cultivated independently, depending on the interests”; violation of any lease term entails the cancellation of the agreement by the monastery; any delay in paying rent entitles the monastery to collect it in accordance with the law “On the Collection of Overdue Treasury Revenues” (Article 106). The simultaneous acquisition by one person of two dwellings registered to monasteries is categorically is prohibited (Article 128). Any new construction or expansion of buildings is carried out only with the permission of the Holy Kinot (Article 129). “All goods imported to the Holy Mountain for its monks worth up to 1,000 gold drachmas per year for each monk are not subject to customs duties; goods in excess of this amount and everything imported by merchants are subject to the general established state taxation” (Article 167). All forest and other products exported from the Holy Mountain are exempt from state taxation (Article 168). “The forests of the peninsula of the Holy Mountain are not subject to forest laws” (Article 169). In recent decades, valuable tree species (primarily Mediterranean pine) have been planted in place of cleared areas. “Fishing on the Holy Mountain for the needs of its monks is free and exempt from all taxes” (Article 170).

Everyday Life

The lifestyle of Athonite monks is subordinated to the primary purpose of their stay on Athos—prayerful service to God (see also the section “Divine Services”). Monastic prayer can be public or private. During public prayers (Vespers, Compline, Midnight Office, Matins, and Divine Liturgy), monks gather in the main cathedral church (katholikon) and the smaller churches (paraklisis) of the monastery. The basis of private prayer is the short Jesus Prayer. The Mother of God, considered the sole Lady of the Holy Mountain, is especially venerated on Athos. The main activity of the ascetics is unceasing prayer. The monastic cell rule (canon) is obligatory for all monks; cell residents do not perform the church services as fully as in monasteries (sometimes they may be replaced by prayers with a rosary). One of the peculiarities of monastic prayer is considered to be prayerful vigil in the second half of the night, when most people are asleep, and unceasing all-night prayer on the most important feast days. The cell rule in the Athonite monasteries is performed primarily with the prayer rope and is accompanied by prostrations (μετάνοιαι, cf. Slavonic). In most monasteries, the rule has two levels: for novices (3-5 prayer ropes, 30-50 prostrations) and for all monks (12 prayer ropes and 100-150 (for Great Schema monks 300) prostrations). In the most ancient cenobitic monasteries, the Jesus Prayer is read as follows: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me.” Prayer of the Most Holy To the Mother of God – like this: “Most Holy Theotokos, save me, a sinner.” In monasteries that have recently adopted the cenobitic rule, the verbal form of prayers may differ slightly. On 12 hundred-strand prayer beads, the prayers are distributed as follows: 9 – to Jesus Christ, 3 – to the Most Holy Theotokos. According to the Athonite tradition, prayers are read quite quickly: 100 Jesus prayers on the beads usually take from 2 to 10 minutes. Prostrations in Greek monasteries are performed on all days, including feast days, except Sundays and Bright Week. The cell rule is performed standing, with the sign of the cross and a small bow from the waist at each prayer. The rule for Holy Communion in most monasteries is read in the church from a book (canon and prayers); In the Philotheus Monastery and some other monasteries (the so-called Philotheite monasteries) – in cell confession using the prayer rope (1200-1500 Jesus Prayers). Another feature of the Philotheite tradition, based on the spiritual tradition of Elder Joseph the Hesychast († 1959), is a nightly cell vigil for 4 hours before Midnight Office: the cell rule using the prayer rope, mental prayer (from 30 minutes to 1 hour, without the prayer rope), and the reading of Holy Scripture and patristic writings.

The frequency of confession in the Athonite monasteries is not stipulated by a single rule and is determined by the spiritual needs of each inhabitant. Confession usually takes place in one of the cathedral chapels or in the confessor’s cell. Confessors in Greek. The monasteries are staffed by abbots and one or two assistants/deputies. As in the Church of Greece, only priests who have undergone the episcopal ordination as spiritual fathers may hear confession at the Apostolic Sacrament (this is also mandatory for a newly appointed abbot before his enthronement). All brethren receive Holy Communion at least once a week (usually on Thursday and Saturday or Sunday; during Lent – at all liturgies; in Philotheite monasteries – four times a week throughout the year). The modern practice of the Greek Athonite monasteries does not require mandatory confession before Communion.

The usual greeting at the Apostolic Sacrament is to say “Eulogite” (εὐλογεῖτε – bless), to which follows the response “O Kyrios” (i.e., the Lord [will bless]); During the period between Easter and Ascension, the greeting is the cry “Christ is risen!” with the response “Truly He is risen!” Those wishing to enter a closed room say, while knocking on the door: “Δἰ εὐχῶν (τῶν ῾Αγίων Πατέρων ἡμῶν)” (By the prayers (of our holy fathers…)), the response “Amen!” serves as an invitation to enter. The Greek word for simple monks is ̀λδβλθυοτεΟσιε, ῾Οσιώτατε or ῾Οσιολογιώτατε (to learned monks), to those holding the rank of deacon – ῾Ιερολογιώτατε, to hieromonks, abbots, archimandrites, etc. – Πανοσιώτατε, Πανοσιολογιώτατε.

According to Athonite custom, deceased monks are vested in the schema and polybaptism (the body is not washed, and the undergarments are not changed) and, with their face covered with a koukul, they are sewn into a ryassa. An icon of the Most Holy Theotokos is placed on the chest of the deceased. The deceased hieromonk is also vested in a stole, a Gospel is placed in his hands, and his face is covered with an aer; the hierodeacon is vested in an orarion and his face is covered with a small veil. After the rite of departure, the body is taken to the monastery crypt. A memorial litiya is served over the grave. The abbot usually delivers a sermon dedicated to the newly departed. Then a slab is placed over the head of the deceased (to protect it from damage), and the body is covered with earth. For three years, the deceased is commemorated daily at the proskomedia, and then their name is entered into a large memorial book, the “Kuvaras” (Κουβαράς). These books, read on memorial Saturdays, contain the names of all the deceased monks of the monastery, dating back to ancient times (for example, in the “Kuvaras” of the Great Lavra, the list begins with the names of St. Athanasius and the monastery’s founders who lived in the 10th century). After the body has decayed, the remains of the deceased are removed from the grave, and the Divine Liturgy is celebrated in the crypt. The head of the deceased, with the name and age inscribed on it, is placed in the ossuary along with the heads of the other deceased brethren, the remaining bones are stored separately.

Undertaken in Greece in the 1920s. The calendar reform did not find support in Athos, and the monasteries of the Holy Mountain continue to use the Julian calendar. In most monasteries, the day according to Byzantine tradition begins at sunset; the difference with European time ranges from 3 to 7 hours depending on the time of year. The Iveron Monastery uses a slightly different, so-called “Chaldean” system. Civil departments on Armenia and some monasteries use European time. The day is divided into three eight-hour periods, set aside for prayer, work, and rest. Old Greek The verse describes the daily work of a monk: “Write, study, sing, sigh, pray, be silent” (Γράφε, μελέτα, ψάλλε – στέναζε, προσεύχου, σιώπα). Each monastery has its own daily routine, prescribed by the internal charter. The schedule of Vatopedi, which was in effect when this monastery was a separate monastery (according to the European count): from 4 to 7 a.m. – matins, liturgy, breakfast; 7-10 – work inside and outside the monastery; 10-12 – household chores, receiving guests, academic studies; 12-15 – lunch and rest; 15-16 – Vespers and Compline; 16-18 – work, walk, visits; 18-19 – preparations for dinner; 19-21 – dinner and classes; 21-4 – canon (monastic rule), private prayer and night’s rest; 4 a.m. – awakening. The routine of the cenobitic monastery of St. Dionysius (according to the so-called Byzantine reckoning of time): from 6 to 7 a.m. after sunset – canon (12 rosaries and 300 prostrations); 7-10 – the service of matins; 10-11.30 – rest in the chambers; 11.30-12 – preparation for common prayer; 12-13.30 – liturgy and service of thanksgiving; 13.30-14 – common lunch; 14-18 – services and obediences; 18-20 – midday rest, classes; 20-21.30 – services; 21.30-22.30 – vespers; 22.30-23.30 – common dinner; 23.30-24 – walk; 24-0.30 – compline, closing of the monastery gates; 1-6 – night rest; 6 a.m. – awakening. The cells follow the schedule established by the elders. Example (according to the so-called Byzantine counting of time): 8.30-10.30 – matins; 10.30-11.30 – canon (rosary and bows); 11.30-12 – breakfast; 12-17 – work (handicrafts or agricultural work); 17-18 – common lunch (which is prepared by one of the members of the synody); 18-19 – rest; 19-20 – Vespers; 20-24 – Labor; 24-1 – Common Supper; 1-1:30 – Compline and Hymns in Honor of the Theotokos; 1:30-3:00 – Studies and Private Prayer; 3-8:30 – Night’s Rest. The schedule is, of course, different on Sundays and holidays. Due to the dependence of the so-called Byzantine clock on the seasons, the daily schedule varies.

Monastic Food

Throughout the year, on Sunday, Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday, two common meals are prescribed – after Liturgy and Vespers; on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday (except for solid weeks), as well as on the days of Holy Lent (except Saturdays and Sundays), one common meal is prescribed – after Vespers (monophagia – monopodia). The daily meal includes wheat bread, water, onions, garlic, salt, and vinegar. Salted olives and fruit are almost always offered (except on days of strict fasting), while vegetables and boiled chestnuts are also offered in summer and autumn. On fasting days, boiled Lenten food is prepared without oil. On fasting days, white or red dry grape wine (1 krasovuli per person), olive oil, a dairy dish (usually sheep’s cheese), and sweets (halva) are offered at the meal. Eggs are usually offered only during the Easter period; fish is served on Sundays and the twelve great feasts (on polyeleos feasts that fall on fasting days, as well as on Sundays of the Holy Forty Days and the Dormition Fast, it is replaced by octopus, squid, mussels, and other seafood). With the blessing of the abbot, the brethren may prepare tea or coffee in their cells. In the Philotheite monasteries, tea is offered in the fraternal refectory on all fast days after the Liturgy. On Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday of the first week of Great Lent, the brethren of most monasteries keep Complete abstinence in food and drink. Hermits and hesychasts follow their own schedules, each according to their physical strength. As a rule, they consume foods that require no cooking (crackers, olives, beans, greens, dried fruits, etc.)—xerophagy (ξηροφαγία); vegetable oil is consumed only on Saturdays and Sundays; food is usually brought to the hermits by passing monks.

At the beginning of each year, the brethren are assigned obediences at the council of each monastery. According to Athonite custom, the inhabitants receive new obediences annually, but if necessary, the council may retain a brother in an old obedience for another year. At the end of the meeting, the brethren enter the abbot’s room in order of seniority and receive a blessing from the abbot (according to the Greek Athonite tradition, by kissing his hand), and he, in the presence of the elders, conveys the decision of the council to each brother. The list of obediences is usually contained in the internal charter of the monastery. It can only be changed by decision of the spiritual council. Most of the work is related to ensuring the worship, preserving the holy relics, and serving the brethren and pilgrims. For example, the charter of the Great Lavra mentions the following obediences: representative of the monastery in the Holy Community; secretary of the monastery; treasurer of the monastery; assistant to the steward (according to ancient tradition, the Holy Mother of God Herself is considered the steward of the Great Lavra); escort of guests; gatekeeper (greets guests, takes them to the hotel – archondarik, monitors the rules of visiting); innkeeper (archondarik, takes care of the food and overnight accommodation of the guests); hegumeniaris (assistant to the abbot); sexton (ecclesiarch); typicar (preparer, oversees the course of the service); vimatar (sacrist, responsible for the care of the holy relics and the altar); cellarer (keeper of provisions); cook; baker; hospital brother and gyrok (cares for the sick and infirm elderly); refectory keeper (oversees the preparation of the common meal, distributes bread); prosphora maker; tailor; shoemaker; arsanaris (caretaker of the ship pier); gardener and vegetable grower; winegrower. Along with these, there are other obediences: bell-ringer; reader; librarian; synodiar (prepares for meetings of spiritual councils); prosmonar of the Theotokos (cares for the venerated icon of the Mother of God, sings prayers, accepts offerings from pilgrims); Warden (in charge of the stables and cattle yard); forester; night watchman, etc. According to the tradition of some communal cells with a small brotherhood, the main obediences (cook, sexton, etc.) change every week. Hieromonks perform the liturgical rotation according to seniority of ordination.

Many monasteries have developed arts and crafts, including icon painting, wood carving, and other crafts. The statutes strictly prohibit the sale of icons and works of art made outside of Mount Athos, as well as their production on its territory by laypeople. Reproduction of Athonite icons on paper without the permission of the monastery is prohibited (Article 174). The removal from Athos of any antiques, manuscripts, icons, vessels, books, and other items listed in the lists of monastic institutions is prohibited.

Common work performed by the entire brotherhood (pankinia): weekly leavening of bread, harvesting grapes and olives, etc. Due to the significant volume of construction, agricultural, and other work, many monasteries are forced to resort to hiring laypeople (primarily outside the monastery walls).

One of the ancient customs preserved in Athos is monastic hospitality. Each Vyatogorsk monastery welcomes all visiting pilgrims and tourists for the night, regardless of religion, nationality, etc. They are provided with a place in a hotel (arkhondariki) and food according to the monastery charter. Arrivals are offered refreshments – coffee, cold water in hot weather, sweets, a small quantity (up to 50 g) of strong alcoholic drinks – ouzo (aniseed vodka) or tsipouro (strong grape vodka). Guests are received free of charge, to the glory of God. All pilgrims are invited to services (in monasteries with a strict charter, non-Orthodox may visit the church outside of service hours). Orthodox can confess and receive Holy Communion, and venerate the holy relics. All guests dine at a common meal with the brethren (non-Orthodox are usually allocated a special table). Pilgrims are provided with the best accommodations (sometimes even private rooms) for monks and clergy. Some monasteries offer talks and tours for guests.

According to the rules of Athonite Monasteries, each pilgrim may stay at any monastery for one night; a longer stay is possible with the blessing of its abbot. Overnight accommodations are available in Daphne and Karyes. To visit Athonite Monasteries, a special permit (διαμονητήριον) is required, which is issued at the pilgrimage service in Thessaloniki. Since the maximum number of pilgrims at Athonite Monasteries is limited, arriving without prior notice may result in delays (especially on the eve of church holidays and during the summer months). Clergy must have a written blessing from the Polish Patriarchate to obtain a permit. Since ancient times, a strict avaton has been in effect on A., prohibiting entry to the peninsula not only for women but also for female animals (Article 186 of the Charter). Persons attempting to violate this prohibition are subject to imprisonment for terms ranging from two months to a year. Vessels carrying women are also prohibited from approaching A.’s harbors and piers.

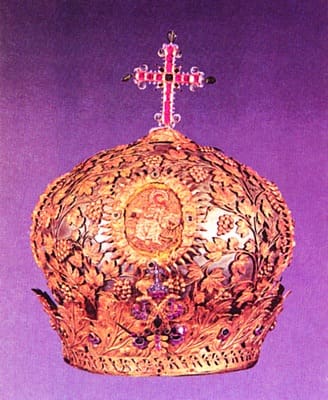

Illustration: Mithra, the so-called crown of Emperor Nicephorus Phocas. 13th century? (Great Lavra).

References: ̓Αλέξανδρος Λαυριώτης (Λαζαρίδης), γέρων.῾Οδηγὸς῾Αγίου ̀Ορους. ̓Αθῆναι, 1957; Θεοδόρου Ε. ̀Αθως, Μοναχικὸς βίος καὶ κανονισμοί // ΘΗΕ. Τ. 1. Σ. 926-928; Доримедонт (Сухинин), иером. Об управлении монастырем; О послушаниях; О монашеском постриге; О келейной молитве; Об исповеди и причащении Святых Христовых Таин; О посте; О странноприимстве // [Хризостом (Кацулиерис), архим., с братиею.] Святогорский устав церковного последования. Серг. П.; Афон, 2002. С. 189-203. Прилож. 1.